The Thaumaturge: how to give weight to simple mechanics through narrative

The Thaumaturge from the creators of the "Witcher" remake is actually a rather small and simple game. Its foundation is a hustle from point A to point B, dialogues with weak non-linearity, and card-based combat. However, the developers skillfully disguised it as something more. Primarily, this concerns artistic design and narrative - they are what make The Thaumaturge something bigger than it actually is.

Narrative Tricks

Jakub Rokosh previously worked at CD Projekt RED as the lead quest designer on the second and third "Witcher" games. Now his studio is working on a remake of the first part. In addition, Fool’s Theory develops games based on their own IP, and The Thaumaturge is one of them.

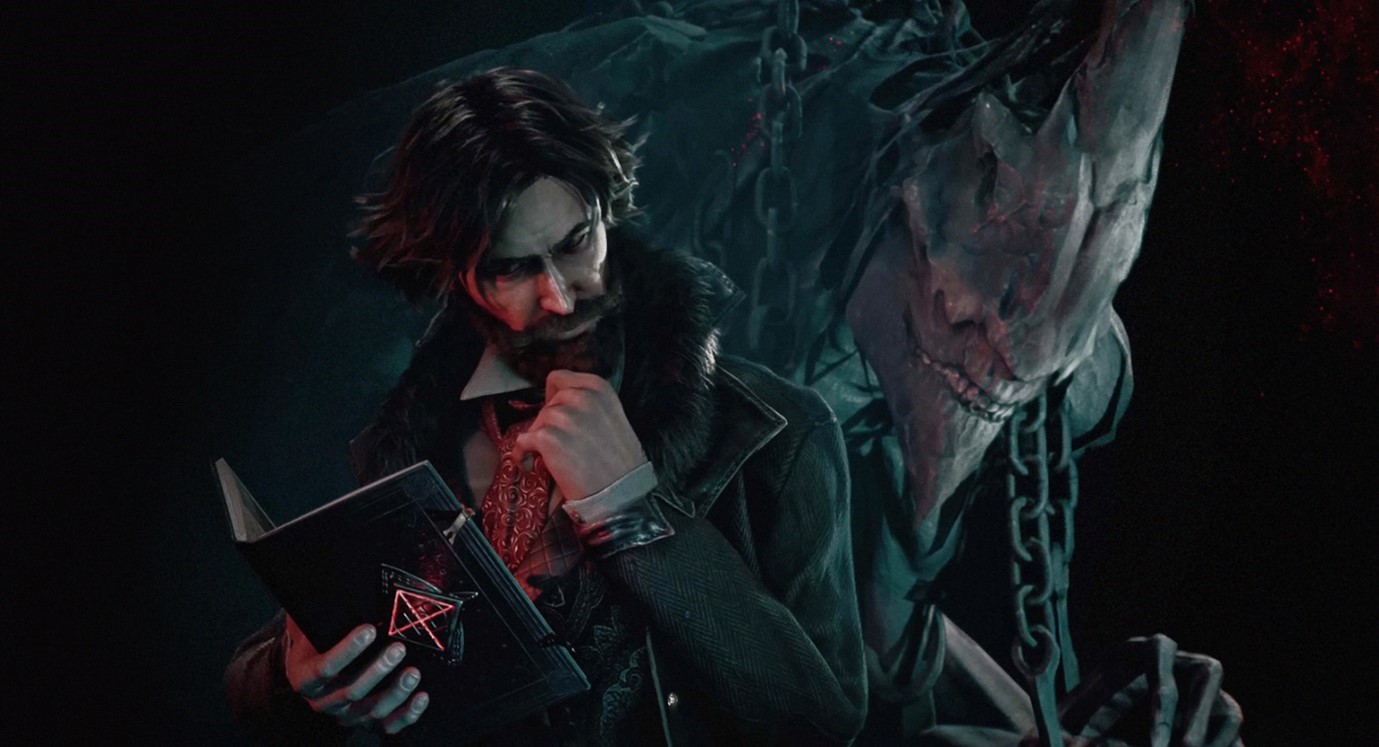

Warsaw, 1905. An alternative history, but not too far from reality. Poland is divided, the Russian Empire reigns in Warsaw, and even Nicholas II personally, but the locals don't like it, and socialist sentiments are growing in the city. The main character is the charismatic Victor Shulsky. He is a thaumaturge - a kind of demonologist who controls salutors (demons in general). Initially, Shulsky has only one salutor - the Upyr, which appeared in his childhood, a skeleton in mechs with a cane. However, as the game progresses, Victor catches several more and will control them, as if they were Pokémon. Grigory Rasputin, who fled to Poland after a scandal in St. Petersburg, helps him tame wild salutors. The basis of the game is the motif of returning home: Victor returns to his hometown to say goodbye to his deceased father, despite the fact that his son did not love him, and it seems to be mutual. The city itself has also changed, and it's not just about the ubiquitous people in uniform. Everything seems to be the same as before but not quite. This motif is familiar to everyone who has ever left their hometown for various reasons. Returning home is always accompanied by a bitter feeling of nostalgia and bright sadness, which narrative designers take full advantage of. Through just one family gathering, they skillfully reveal each of the attendees - through the division of the deceased's property and condolences. You immediately sympathize with Victor; he has conflict and trauma from the past. And even a close childhood friend now wishes Shulsky to burn in hell.

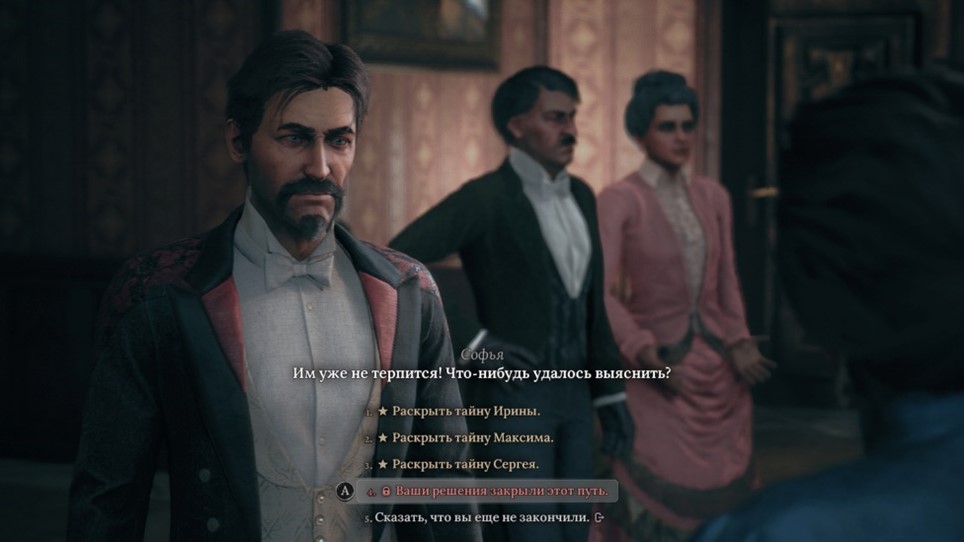

Shulsky himself has a flaw - pride, thanks to which the Upyr attached itself to him. Ordinary people do not see salutors but feel their influence: they attach themselves to the flaws of their victims' characters. This could be deceit or cowardice. Thaumaturges not only see salutors but also use them for their own purposes, relieving people of flaws (essentially getting rid of negative traits) and managing the monsters that feed on them. Throughout the game, Shulsky collects salutors. However, only pride is manifested in dialogues. At the same time, it intensifies: the more often you choose this path in dialogues (which initially often leads to a fight), the more flaw points you get. Little pride - some options will be blocked. A lot - other options will be blocked. But much more interesting are the four paths of character development: heart, mind, deed, and word. Each path has its own skills that will be useful in battle. They also correspond to their own salutors. The Upyr, for example, is responsible for the heart, while Veles, taken from a bohemian intriguer, is responsible for the word.

These indicators determine the combat techniques, dialogue options, and observations when searching for clues that Shulsky discovers in his small investigations. In fact, there is nothing new in such a leveling system, but all mechanics are subordinated to one narrative concept and therefore perceived as a whole.

The concept is interesting, making it seem like you're playing The Council with its branching role-playing system. And the setting is similar. Although these are just opening and closing dialogue options, which change little, but are original in their design.

This is entirely the merit of the narrative designers. They could have simply made a hero/villain path with a scale, as in Knights of the Old Republic, and left the leveling purely for battles. They could have even not bothered and just let the player train salutors as if they were Pokémon, and that's it. But the authors came up with a holistic concept that affects everything at once - both battles, dialogues, and the investigation element. These are all primitive mechanics, but together they bloom and complement each other thanks to narrative findings. The work becomes holistic, thoroughly thought out.